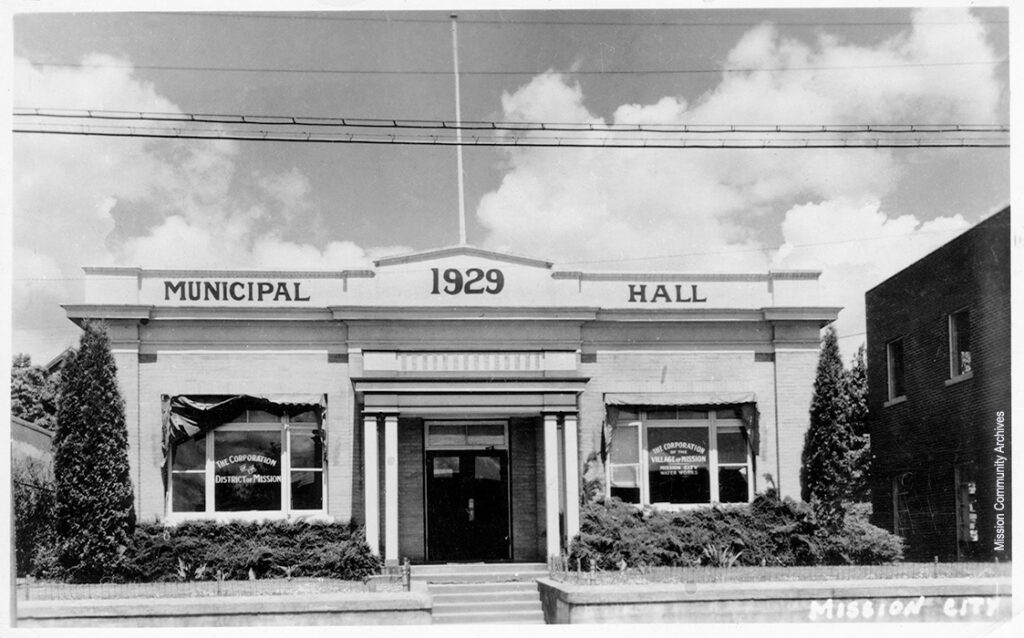

Just before the celebration of the coming of the New Year, 1930, Mission was busy celebrating the opening of its newly constructed municipal hall. Mission at the time had a considerably different governing system than we have in the present day. Mission as we know it today was actually two distinct entities. The Village of Mission, as well as the Corporation of Mission.

The Village of Mission was the area where the current Downtown/ First Avenue core resides and was the business centre of town during the Depression era. The Village government was headed by a person occupying the title of Chair. Over the decade, the Chair role would be filled by:

● Aja Lane 1929-1932

● John Catherwood 1933-1934, 1938

● Andrew Graham 1935-1937

● Robert MacRae 1939-1942

One of the changes the village chair and the commissioners implemented during the Great Depression was the renaming of some street names. When By-law No.53 was authorized on February 2, 1932, streets that had been named after American influences would be replaced with more appropriate names. The streets Washington, California, and Seattle would become Main, Second, and Third respectively. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, Mission was shaping its identity, and chosing its influences.

The area surrounding the Village, from Stave River to Hatzic Lake was considered the Corporation of Mission. Its political structure was different and its governmental head occupied the position of Reeve. The Reeves over the same time period were:

● W. Harvey Wren 1924-1936

● J.W. Doyle 1937-1937

● Albert Catherwood 1938-1951

Harvey Wren, the long serving Reeve, would make sure during his tenure that the municipality of Mission would keep its larger community in mind through tough times. Some high-profile citizens wanted the municipality to return to a “ward system” where the various regions held their own elections and looked after their own affairs. Wren realized that it would be better for places like Steelhead, Silverdale, or Hatzic to band together and focus on bigger picture ideas that could bring everyone together rather than isolate themselves for small interests. Harvey Wren’s ideas rang true to his constituents and he was well liked and respected in Mission. After his untimely death in 1937, the city would see its largest attended funeral to that point in time.

These men and their administrations left their marks on Mission in various ways, and following different visions. A drive around Mission today will have you possibly passing by one of the roads named after many of these leaders of Mission through the Great Depression

The building of the Municipal Hall symbolized the cooperation of the two governing entities to work together towards a better future for both. Both governing institutions were housed in building to allow easier communication and work together. We would continue to see the spirit of cooperation throughout the entire decade as Missionites banded together in unions and relief organizations that would often work closely with town officials and trade boards to come up with ways within the community to deal with the needs of all, local and passerby. Far from the welfare state of the post-World War 2 period, Canadians could not rely on their Federal and Provincial governments to provide much of the aid they would need to survive the Depression, so they turned to each other. Organizations like Comets (Count On Me Every Time) were looking to make sure Missionites’ needs were not going unmet and when times did get difficult would come together with other organizations and local governments to figure out how to plot a best course of action. The Mission Hospital with aid from the local businesses, government, and community, also stepped up in its aid for those who needed it. Knowing some may not be able to pay hospital fees and dues in money during the harder time of the Great Depression, they began accepting produce that they would then preserve by canning or jarring, then use that “payment” to provide for any hungry mouths that needed feeding.

“It was the policy of the Hospital to provide two sandwiches, fruit and whatever sweets were on hand.”

Services for locals were growing in demand, but so too were the demands produced by the influx of outsiders riding on the rails. Local historian Catherine Marcellus estimated that,

“it is probably correct that more men stopped in Mission than at any point between Vancouver and the Interior for this was the last major farming area that the [Canadian Pacific Rail] passed through before it came to the Fraser Canyon.”

The Mission Hospital was not about to move away from its pledge of helping anyone who needed care. The governing institutions of Mission worked for the care of residents and non-residents during the time, and while not always perfectly, it was these cooperative efforts that allowed Mission to avoid the relative the worst of the privations suffered in a so many other places.